Child-Abuse Prevention

By Rick Braschler

Historically, when it comes to state laws dealing with child-abuse prevention initiatives, there are two that typically take center stage:

Photo: © Can Stock Photo / jmpaget

1. Background screening

2. Mandatory reporting.

While they still have a place at the table of all child-protection tactics, these methods are unfortunately connected to opposite ends of a challenging legal system that offers diminishing returns. In this article, I will examine some challenges to these age-old tactics, shed light on the abuser-behavior path, and spotlight three stages of abuse prevention.

Challenges To Age-Old Tactics

In the early 1990s, background screening emerged as perhaps the most highly touted prevention tactic. It seemed logical then—and still seems today—that knowing the criminal history of a potential employee would assist youth organizations in screening out those deemed ineligible to work with minors. And yet, while screening companies have advanced in technology and services, they are still bound by one challenging reality—the successful reporting and conviction of offenders. Unfortunately, the national criminal conviction rate of less than 10 percent for reported sex offenders leaves many without a criminal record to report.

Like background screening, mandatory reporting is tied to the same fate in its endeavor to prevent child abuses. Both methods lean heavily on the court system and its success in resolving abuse through prosecution and conviction, followed by criminal records and screenings. Not only are both approaches plagued with poor conviction outcomes, but even when successful, offender recidivism after incarceration prolongs the impact.

With background screening initiating staff eligibility, and mandatory reporting severing this eligibility, these now serve as bookends by which to explore the elements of human interaction between adults and children within a youth program. More specifically, how does one travel from being screened eligible to reported ineligible, fooling everyone along the way, and what can be done about it?

The Abuser Behavior Path

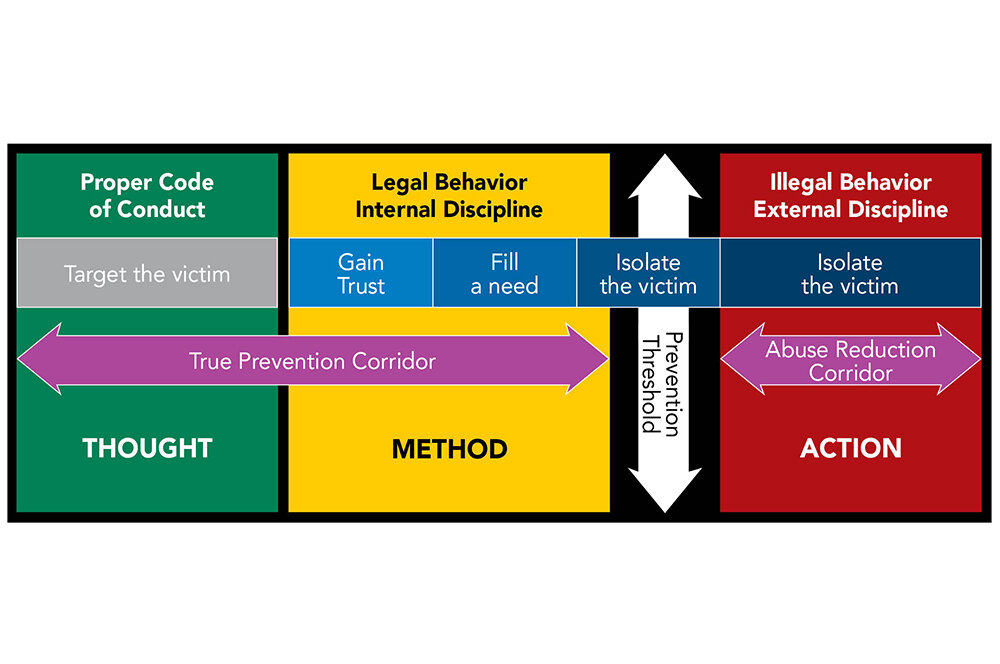

The Abuser Behavior Map illustrates the path and process that an abuser must navigate in order to move from appropriate behavior (trust building) to illegal sexual acts. The green shaded area represents legal and acceptable behavior as defined by cultural expectations or program guidelines that comply with state laws and promote healthy outcomes for children. These appropriate codes of conduct should be outlined in camp-staff training in what is referred to as “Touch, Talk, Territory.” In other words, it identifies how to appropriately touch a child (e.g., high fives), talk to a child (e.g., encouraging words), and defines appropriate territory (e.g., public interaction).

The yellow shaded area represents legal behavior, but may include suspicious, non-compliant, or inappropriate undertones or patterns that are not illegal, nor are they reportable, according to most state child sexual-abuse laws. The yellow area can be categorized as inappropriate codes of conduct outlined in camp training in order to teach staff how not to touch, talk, or be alone with campers (territory). Infractions in the yellow area can include written or verbal warnings as well as termination from employment.

Lastly, the red shaded area represents illegal behavior as defined by state statute and is reportable and punishable by law.

Abusers will often exhibit noticeable behavior actions in the green area in order to establish needed trust from bystanders and gatekeepers. Once trust is established, they will need to exploit opportunities in the yellow zone pressing against codes of conduct.

The green/yellow areas represent the landscape whereby the first four stages of victim grooming are carried out. Abusers may exhibit subtle, but perhaps noticeable behavior actions on the yellow/red boundary while exploiting weak protective measures, as well as groom potential victims in progression to stage five of the grooming stages.

In order to prevent child-abuse scenarios, youth-serving organizations, children, and parents must collectively engage in effective strategies within the True Prevention Corridor (TPC).

The True Prevention Corridor denotes the span of time between peer/peer or adult/child appropriate interaction leading to illegal behavior. (See purple shaded area.) The TPC may span minutes, hours, days, weeks, or even months, and is subject to the type of molester, the method of grooming and boundary reduction, the vulnerability of victims, and the effectiveness of parental or organizational child-protective measures. Effective measures taken within the TPC can resolve potential episodes of abuse in early-stage behavior or policy infractions before the Prevention Threshold is reached. The Prevention Threshold represents the boundary where adult-driven methods for abuse prevention have failed, and potential victims must be equipped and empowered to recognize, resist, and report uncomfortable or inappropriate behavior.

Stages Of Abuse Prevention

Now that the Abuser Behavior Path has been identified, prevention strategies within each zone can be implemented:

1. Thought Resolution: Stage-one abuse prevention (see yellow shaded area) strives to provide an opt-out opportunity with remedial solutions to those in the society contemplating a sexual encounter with children. This is true abuse prevention in that it solves the threat of abuse at the root level rather than at the reporting level. Such staff members are encouraged to leave the program and seek counseling or risk the consequences of acting upon their thoughts.

2. Method Resolution: Stage-two abuse prevention (see purple shaded area) combines the framework of stringent behavioral policies with effective bystander-monitoring protocols to detect suspicious or inappropriate behavior or a breach in conduct policies, which can be resolved prior to an occurrence of abuse.

3. Action Resolution: Stage-three abuse prevention (see red shaded area) is regarded more as “reduction” than “prevention” in that it responds quickly to reporting to authorities in the event that inappropriate or suspicious behavior has occurred.

Ultimately, the successful execution of protective elements within these three prevention stages may produce one or more of the following abuser remedies:

1. Screen out: A person is denied access to minors due to a negative background screen, reference, work verification, or red-flag indicators.

2. Opt out: A person opts out of working or volunteering at a youth organization, or from engaging minors inappropriately.

3. Monitor out: A person is removed from access to minors resulting from suspicious behavior and/or inability to comply with organizational expectations or policies.

4. Report out: A person is reported by a third party or victim and is removed from access to minors and placed under legal investigation.

While background screening and mandatory reporting are essential elements to child-abuse prevention, there is still much to do between these bookends. Understanding the abuser behavior path in moving from appropriate to legal to illegal behavior is critical in helping camps to establish effective child-protective systems. And, while one can hope for more effective screening, treatment, or prosecution outcomes to help wage this war, it is clear that camp leaders are very much on the front lines.

Rick Braschler is co-author of the “Child Protection Plan,” and is a subject-matter expert on child-abuse prevention plans for youth-serving organizations. Reach him at rick@kanakuk.com, or read more about The Child Protection Plan at www.kanakukchildprotection.com/plan.